Kate Corbett Pollack is a graduate student in Cultural Foundations of Education and Disability Studies at Syracuse University. Her scholarship has grown from Josiah’s story, and has led to an interest in prisons, mental illness, social reform, education and disability. She wrote a monthly blog for almost three years, which can be viewed at americanpomeroys.blogspot.com, the blog for the American Pomeroy Historic Genealogical Association. She has also written for and done work with the Landmarks Society of Greater Utica on the history and families who lived in a few of the beautiful old mansions in that area. Prior to coming to the university, she lived in Brooklyn, and before that Eugene, Oregon where she was born, and Utica, New York. Her family in Syracuse goes back one hundred years, and she has lived here over the years on occasion.

To view and comment on Kate’s posts individually, follow the links below:

April 2015

Fifty Seven Years in a Cage: A Story of Psychiatric Disability from the late Puritan Era (10 Apr. 2015)

Only a Being of Senseless Existence: The Continuing Story of Josiah Spaulding, Jr. (28 Apr. 2015)

“While the dearest of friends lays in the cold ground”: Epidemic Disease, Incarceration and Patriarchal Control; The Continuing Story of Josiah Spaulding (4 May 2015)

Fifty Seven Years in a Cage: A Story of Psychiatric Disability from the late Puritan Era (10 April)

My historic work is not about famous able-bodied men, battles or presidents as many think of when they think of history; it is about women, epidemic disease, art, slavery, mental illness, reform and disability. It is about those were marginalized, the ones lost to history whose stories have been long forgotten or never told. The medieval anchoresses who lived in little rooms, those kept in towers, in prisons, in asylums, those who were physically or socially incarcerated. As a genealogical researcher in North Syracuse, I worked primarily with a collection of one hundred and forty four letters written by four generations of Massachusetts women in the late eighteenth through mid nineteenth centuries, which centered my work on Puritan New England. The collection had been long forgotten until its discovery about four years ago in an Arizona attic. Within the still pristine letters, preserved by dry heat, was the story of the Spaulding family of Buckland, who kept their only son in a cage in the family home. Josiah Spaulding was said to be insane, and remained in the cage for fifty-seven years until his death. The letters were mostly written by his four sisters. I hope to tell some of their stories here.

What are the circumstances that would compel a family to imprison one of its members in an iron cage for the rest of his life? In the case of Josiah Spaulding Junior, born 1787, the answer given by his preacher father, Reverend Josiah Spaulding of Buckland, Massachusetts, was that his son had “lost his reason” and was a danger to the family. Later census records on the Spaulding family state that Josiah was insane. Perhaps he was, perhaps he wasn’t. I uncovered this story during my time as an archival researcher for a private archive in North Syracuse, where we received one hundred and forty-four letters written by four generations of Spaulding family members. In researching this story, I have been unable to find evidence for violent mental illness, but I have found evidence of many other things. Josiah was kept in a cage by various family members in their homes for fifty-seven years. He was put into it when he was about 23 years old, and it is there that he died.

Josiah Spaulding, Jr., the son of a prominent reverend, was expected to follow a certain life path. He was the only surviving infant of a triplet birth, born to Mary Williams of Taunton, Massachusetts and Reverend Spaulding, originally of Plainfield, Connecticut. Josiah’s sister Mary, the firstborn child, had been born the year before. The two maintained a close friendship for many years. Both of Josiah’s parents were from respected lines of New England families who were among the first white settlers of the region, and their genealogies span to the early seventeenth century in America.

Reverend Spaulding was a staunch Calvinist, and obtained his Doctor of Divinity from Yale in 1778. He was ordained as a minister in 1782 and had gone to Uxbridge, Massachusetts to begin his career as the local minister. He was married there, as well. However, as would occur repeatedly until his arrival in Buckland, the reverend was dismissed from his position in part because of “unpopularity due to his Calvinist theology”, according to the Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College, and the fact that he was thought to be eccentric. Hardline Calvinism, which had long been the established religion in New England, was slowly starting to fall out of vogue during this period. According to records, parishioners had a hard time believing that God “foreordained every thought, word and action” of human beings, as Calvinism and the Reverend taught. However, Reverend Spaulding deeply believed in the doctrine and would not renege even a little. As a result, he had to move around a few times until the family settled in Buckland, where he remained minister for twenty-eight years and was widely loved by the townspeople. Josiah was eight years old when the Spauldings arrived in Buckland. Daughters Nancy, Deborah, and Lydia had been added to the family, with Lydia being the youngest, born in 1799.

Letters between Josiah and his older sister, Mary, demonstrate a close relationship between the two. Mary’s 1801 letter to Josiah, written when she was sixteen and he around fourteen and away at a conference in Goshen, spoke heavily of religion and repentance but also of local gossip:

PS I will inform you of the death of Betsy Stinn, she died not long before thanksgiving & it is expected that Lydia her sister is or will soon be married to the gentleman that courted Betsy. & What do you think of that, it has occasioned considerable talk here…

As a young woman of this era, Mary would not have been groomed for a career in the way that Reverend Spaulding was doing by bringing his son to a religious conference. Unlike her mother and namesake Mary Williams, Mary Spaulding was taught how to write and had beautiful penmanship. She and her sisters attended the local one-room schoolhouse in Buckland where a peer of theirs was Daniel Forbes, famous for his penmanship and friends with the Spaulding family. There is little doubt that the Spaulding children learned penmanship in some measure from Daniel, and in the Spaulding collection there are letters written by him to Mary. However, the Spaulding daughters’ education did not go much beyond their years at the local schoolhouse, as they were expected to excel instead in the domestic arts and get married.

Josiah, also expected to marry and raise a family and continue the Spaulding lineage, could attend college. Neil Perry’s 1966 article on Josiah for the Springfield Morning Union, based on Victorian era articles from one hundred years prior, states that Josiah was violent and rebellious in his youth, and was not accepted to college. These descriptions are from 1866, just before Josiah’s death. However, the language of articles like these is typical to language of the Victorian era when describing or reporting on mental illness, and Josiah is referred to as “deranged.”

The family letters indicate otherwise. Josiah was an articulate and intelligent young man who worked as a teacher, and had the most beautiful penmanship in the family. The story of Josiah will continue in a three part series on this blog. Perhaps he did have some mental illness, and he did seem to be rebellious for the era. It is my estimation that his aversion to Puritan based norms and expectations and his conflicting ideology from his father’s was the real reason that he was caged, along with what does seem to be some kind of possible psychiatric issue. However the description of him as violent and deranged was sensationalized, and is not an accurate description of those with psychiatric disabilities on the whole. There has long been, and continues to be a disparity in power between those who are considered to be able bodied and minded, and those who aren’t. The Spaulding family was absolutely dominated, as most Puritan lines were, by the patriarch. It is not Josiah that should necessarily be looked to as defining derangement, but his Calvinist father, who not only was the patriarch of the family, but of the entire village of Buckland and much of western Massachusetts.

[I will continue my exploration of Josiah and his family in next week’s post.]

Only a Being of Senseless Existence: The Continuing Story of Josiah Spaulding, Jr. (28 April)

Mary Lyon Church in Buckland, Massachusetts, originally called the First Congregational Church of Buckland.

Reverend Spaulding was the minister therefor 28 years.

Josiah Spaulding outlived almost everyone in his family by many years. He was about age 81 when he died, and at that time had been put on display at the Deerfield Poor Farm, where admission was charged to see him. Massachusetts journalists traveled to the area to view Josiah and write articles about him, but the reality was that no one really knew much about his early life. There was no one in his family left to ask, and the villagers probably had little idea of what had happened back in 1812 when Reverend Spaulding caged his son, as it was an event that occurred behind the closed doors of the parsonage. Popular perception and belief in 1866 was that psychiatrically disabled people were “lower than brutes,” were insensate, and of course, not at all intelligent. One reporter however, wrote that he was surprised upon viewing the elderly Josiah Spaulding, who by then had spent almost fifty seven years in the cage, due to the “sharp and quick mind” he saw before him. Evidently Josiah fixed his clear gray eyes upon the reporter in a steady gaze, but it does not seem as if he said anything. It was the look alone that rattled the reporter, and one can only imagine how it felt.

By 1808, Josiah Spaulding Jr. had gained a position as a teacher in nearby Plainfield. Newspaper articles written in 1866 state that Josiah was not accepted to college because he was a raving maniac. I am unsure if Josiah attended college, but my estimation due to research is that he may not have. By the time Josiah had reached young adulthood, Reverend Spaulding had found a place among the New England Divines, and had gained respect and influence in Western Massachusetts. A teaching job in Plainfield could have easily been procured for him through his father’s connections whether he had gone to college or not. Josiah’s education in Buckland also would have been enough to curate his intelligence, which, based on his letters, was ample, and could facilitate a teaching job.

Reverend Spaulding, in an 1808 letter to written to Josiah while he was away at his teaching job, addressed the epidemic disease so prevalent in Buckland during these years. The Reverened believed that the disease was God directly killing people:

My dear Son,

The Lord keeps us alive, We are all of us still alive and in a measure of good health, which is thro’ the tender mercies of our God. There appear to be a calamity upon us, and the hand of God out against us; which ought to be for our humiliation, and prayerful consideration. I think that you, nor any of us, ought to despair, or to doubt the mercy of God, we may be guilty of great sin in this way.[1]

During these years, the epidemic disease that absolutely ravaged Buckland, written about in the Reverend’s above letter, could not be explained by science, as the tools did not exist. Reverend Spaulding, and by extension, the villagers of Buckland, believed that God was angry and killing people. In the Reverend’s 1808 letter to his son, he implores Josiah to not anger God any further, and to “prayerfully consider” the reason that God was striking people down. Josiah’s belief that God was loving would not have functioned to explain the constant disease and death in the village in the eyes of his father. For Reverend Spaulding, his son’s doctrinal rebellion was not only disobedient to him, it was disobedient to God, and disobedience to God during this time would result in direct, fatal consequences.

The Spaulding Family’s Graves

Josiah’s response, dated June 15th, 1808:

You think that I, or no one, ought to despair in the mercy of God, nor doubt his goodness…I think this is true, but all the impenitent ought to doubt, while they remain in sin, that they shall not be saved unless they repent…

According to Professor Philip Grevin of Rutgers University, who has written extensively on Puritan childrearing tradition, questioning the patriarch at all was gravely sinful and disobedient. Reverend Spaulding never relented even a little in his hardline Calvinist beliefs. Josiah and his friends, like the minister Ezra Fisk, wrote more about the loving nature of Christ and forgiveness. This was a doctrine different from Reverend Spaulding’s–and to differ even a little from Reverend Spaulding’s doctrine would be considered very rebellious in this era, especially by the Reverend himself.

More evidence of Josiah’s intelligent, caring nature appears in his 1806 letter to his sister Mary, written in gorgeous, flourishing, and artful script:

Dear Sister. Whilst the morn arises and the sparkling sun shines around my habitation I converse a moment with a dear Absent sister, your letter I received with pleasure and happy would my state be if I truly considered those things which you wrote to me about…may Christ grant me and you a blessing that we may truly love him for he is worthy of all our love…I rejoice to hear of your health and all the rest of the family and that I in measure enjoy mine.[2]

Based on Josiah’s words to Mary in his above response to her, it seems as if she may have been gently giving him some kind of advice, which would be consistent with his un-Puritan behavior or his identity in the family as the different one. When he responded that he would be happier if he followed her advice, perhaps he meant that yes, he would be less stressed if he conformed to expectations. Mary was very aware of the Reverend’s personality and role as patriarch, and what that meant–and therefore, she was likely worried about Josiah.

In 1810, Mary Spaulding married Isaac Pomeroy of Southampton, Massachusetts, and moved to that village, which was 30 miles south of Buckland. Josiah followed her move, and often joined Mary in Southampton–so much so that he kept clothing at Mary and Isaac’s house and possibly had his own room there. It does seem as if Josiah was struggling with mental illness of some kind, as his sisters wrote to each other out of concern for Josiah’s “lost reason,” and the “pills and drops” he was taking for it. Josiah was about 23 when these letters were written, the age that psychiatric disabilities like bipolar or schizophrenia often manifest.

Reverend Spaulding meanwhile, was busy crafting his three hundred-page book on the nature of hell and suffering, and seething over Josiah’s choices. In 1812, he would put a permanent stop to Josiah’s visits to Mary, sending youngest daughter Lydia there to collect him. When he returned home to Buckland, his father would forcibly chain Josiah to the floor of his bedroom in the beginning of his attempt to exert total control over his son.

[I will conclude my exploration of Josiah and his family in next week’s post.]

[1] Reverend Josiah Spaulding, letter to Josiah Spaulding, Jr., 21 May 1808, American Pomeroy Historic Genealogical Association Collection (copy), Sussana Cole Letters, 18080521 Rev Josiah Spaulding to Josiah Jr.(North Syracuse, New York).

[2] Josiah Spaulding Jr., letter to Mary Spaulding, 24 December 1806, American Pomeroy Historic Genealogical Association Collection (copy), Sussana Cole Letters, 18061224 Josiah Spaulding to Miss Mary Spaulding (North Syracuse, New York).

“While the dearest of friends lays in the cold ground”: Epidemic Disease, Incarceration and Patriarchal Control; The Continuing Story of Josiah Spaulding (4 May)

After Josiah Spaulding, Jr. was chained to the floor in his room in about 1812 by his minister father, he would never again live a life unfettered by his father’s religious and patriarchal control—a control which extended over the Spaulding family long after the Reverend’s death in 1823.

Oral history of Buckland tells the tale of Josiah’s early escape attempt: he rubbed his chains against the wooden floor in his bedroom for about a year, finally breaking them. This story is recorded in Neil Perry’s 1966 article for the Springfield Morning Union. While there is much sensationalism in any newspaper article written about Josiah, my trip to the Spaulding house in Buckland in 2012 led me to believe this had actually happened.

After some research, I managed to locate the owner of the former parsonage, built in the late 1700s, the home of Reverend Spaulding, Mary Williams and their children. There has been very little restoration or modernization done to the former Spaulding home. I was invited there by its owner at the time, Edward Purinton, whose family goes back two hundred years in the Buckland area. Ed grew up in Josiah’s room and his mother had been a local Spaulding researcher. She collected funds from the community to install a gravestone for Josiah in the churchyard cemetery alongside his family, for Josiah, who died at the Deerfield Poor Farm, was buried in an unmarked grave.

Ed told me that the room was very cold in the winter, and in the letters, Josiah’s sisters often expressed concern that he stayed warm enough. Josiah’s bedroom still had the original wide-plank floors, the type of which is no longer seen in the United States. Ed moved the bed out of the way, and there underneath were the chain grooves made by young Josiah, who had been chained in front of the fireplace.

The grooves in the floor where Josiah scraped his chains.

According to legend, Josiah managed to break his chains after he rubbed them into the wooden floor. He escaped from his bedroom out the back staircase, which was situated very close to his bedroom and would have been easily reached. The original hardware was still on the doors of the house, and Josiah’s bedroom only had a latch—typical hardware of the late 1700s in this region. The back staircase did indeed open to the kitchen, where the back door was about a foot away. The barn was also very close to the house; here, Josiah attempted to take the family horse and ride to freedom. According to oral history, a neighbor commandeered Josiah and brought him back to the Reverend. Next door to the Spaulding house is an early nineteenth century house that would have been there in 1812. Josiah’s sister Lydia is said to have alerted her father of his escape, and in the commotion, the neighbor came out to tackle Josiah.

The villagers of Buckland were all aware of what had happened to Josiah; they knew that he was “insane,” and that the Reverend was keeping him chained up. It may be hard to believe that the villagers did not think of it as abusive, but at this time, they did not view it that way. Instead, church records and biographies of Reverend Spaulding refer to his “affliction,” his punishment from God: his son, Josiah Jr. Just like epidemic disease in this era was not understood to be biological in nature, mental illness was believed also to be something that God put upon a family. These afflictions were not anyone’s business to interfere with, especially not if it was the family of the highly revered local minister. Reverend Spaulding spoke from the pulpit about what had happened with his son and his version of events is what everyone believed, although it is unclear exactly what he may have said. Whatever he said, it did not elicit sympathy for Josiah. The sympathy was for the Reverend.

After Josiah’s foiled escape-attempt, Reverend Spaulding knew he had to contain him in something much stronger and harder to escape, so he had an iron cage built by the local blacksmith. In this very small, rural village, the blacksmith and the villagers all would have known exactly for whom they built the cage. It was delivered to the Spaulding home, probably carried there, and strong men assisted the Reverend as they forced his son into it. Once Josiah was put into the cage, his relationship with his sisters and his friends effectively either ended completely or was greatly changed. Letters from Josiah’s friend Ezra Fisk were no longer sent to the Spaulding house and Josiah’s correspondence with his favorite sister, Mary, also ended. The horror and desperation Mary must have felt upon learning that her brother had been put into an iron cage one can only imagine. It most likely only compounded her own feelings of being trapped, isolated, incarcerated in the patriarchal world of the early 1800s in which she could not attend college, work, or be independent of men. There was absolutely nothing Mary could have done about her brother’s situation—and she knew it.

Shortly after Josiah was caged, Mary’s husband Isaac died at age thirty-three from what I suspect may have been cholera or dysentery, when Mary was pregnant with her second child. Their three-year-old daughter also died of disease around the same time. At this time, Mary wrote one of the most heartbreaking letters of the collection to her parents, in which she implored them to help. Mary was entirely alone in Southampton with her second child. Her handwriting was wild, and her tone was of arrant, devastated and hopeless emotion, the kind that occurs only after a remarkable tragedy like what she had experienced: she lost almost everyone important to her in a matter of a few years. Mary had little choice but to return home to Buckland to stay with her parents. Upon her return the family home, she was met with the reality that her brother was now in an iron cage, and that was where he was going to stay for the rest of his life. I do not think that Mary ever recovered from any of these events, and she died at age thirty-nine. None of the Spaulding women survived past the age of fifty.

The Spaulding Family graves

I often wonder if Mary talked to her brother after he was caged, or if he implored her to let him out. The Spaulding daughters and their mother, Mary Williams, were in charge of keeping Josiah clothed, fed and warm. They did his laundry, stoked the fireplace, and cared for him. Josiah was not at all a “raving maniac”; he was not a “lunatic”; and there is no evidence that he was ever “deranged”—whatever those words mean. He was guilty, as his father would have said, of great sin: for being different. He was guilty of running off to Southampton to have fun, of not sharing his father’s Calvinist beliefs, of what may have been possible homosexuality based on the letters that were sent to him by a seemingly infatuated Ezra Fisk. The possible outcome of all of this, as Reverend Spaulding knew, was a challenge to the indomitable religious, patriarchal hold the Reverend maintained over his family and the village. It was such an incredible hold, made stronger by its ultimate physical manifestation in the form of Josiah’s cage, that it continued to socially incarcerate the Spaulding family for decades after the Reverend died. Reverend Spaulding’s death in 1823 around the same time as his wife’s death, did not mean a release or reprieve for Josiah, who by then was in his forties. The next generation cared for him, in his cage, as Josiah was transported up the hill to his sister Lydia’s house after the death of his parents. He was taken from the cage, his limbs long atrophied, carried up the hill by villagers, some of whom also carried his cage, in a grim procession to his destination at the home of Lydia. They lived right across the street from the First Congregational Church of Buckland, where the Reverend had preached for twenty-eight years. In its shadow, Josiah would live out the second half of his adult life.

Disability history is imperative to the field of Disability Studies, especially when there is primary source material like Josiah’s letters. In this case, a researcher can analyze his life in a more direct fashion, and also can learn from the letters of his family. If we were to read only newspaper articles and biographies of Reverend Spaulding and Josiah, we might come to the conclusion that Josiah really was violent and deranged, and that his poor father had no other choice but to cage him. Understanding that people with psychiatric and other disabilities are often very intelligent, observant, caring and nonviolent people is imperative to creating and fostering a world where disabled people like Josiah are given the resources they need to achieve contribute to what Disability Studies scholar Rosemarie Garland Thomson would call a biodiverse world. Diversity amongst humans and perspectives of those who think differently or experience the world differently are an important part of fostering intellectual development for all humans. Presuming the competence of those with disabilities, as former Syracuse University Dean of the School of Education, Douglas Bicklen, would say, is a great way to start the process of biodiverse societal inclusion. Josiah’s letters clearly disprove presumptions of derangement, being “lower than a brute” and “insensate.” However, portrayals of psychiatric disability from the nineteenth century and before have continued to create stigma and bias today. Understanding the history of these perceptions and biases and where they began is necessary to unravel them, and see—really see, without presumption —the lives and experiences of disabled people now and in the past.

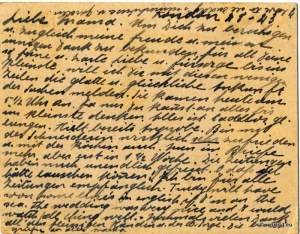

The cover photo is the room where Josiah was kept.