Peter Katz was the editor of Metathesis (2014-2015). His dissertation focuses on sensation fiction, the history of science, and the history of the novel. He fills in intermittently as a writer for Metathesis.

To read and comment on Peter’s posts individually, use the links below:

Regeneration, Rebranding, Republicans; or, Reince Priebus is not your boyfriend (7 Nov. 2014)

“Show me a good time?”: Madonna, Drake, and Police Brutality (18 Apr. 2015)

The Dust-Heap of the Database and the Specters of the Spectator (8 May 2015)

Regeneration, Rebranding, Republicans; or, Reince Priebus is not your boyfriend (7 Nov 2014)

In case you were camping over the last three days, the Republican Party took control of Congress on Tuesday night. To paraphrase an oft-heard line on the Capitol floor, I’m not a social scientist—so I’m not interested in the actual, complex causes of the victory. I am, however, interested in the rhetoric around the victory, particularly the conversation about Republican “rebranding.” On 2 October 2014, Reince Priebus, the Chairman of the Republican National Committee, introduced the next in the cycle of what MSNBC called “A Perpetual State of Republican Rebranding”:

Republicans will unveil a rebranding effort Thursday aimed at changing its image as a political party focused solely on obstructing President Barack Obama’s agenda to instead a champion of ideas and action.

The idea that a party is a brand suggests that voters are consumers, that politics is a commodity to be sold and bought. To think about rebranding and the rhetorical commodification of politics, I turn to an unlikely pairing: the BBC’s Doctor Who.

A little more than a month before Reince Priebus rebranded the Republican Party for the umpteenth time, the Doctor rebranded for the twelfth. A core mechanic of Doctor Who is the Doctor’s “regeneration,” his ability to reincarnate whenever he suffers serious injury in the plot—or more importantly, when the actor playing the Doctor changes. Between series 7 and 8, the 11th Doctor (Matt Smith) gave way to the 12th (Peter Capaldi), to the chagrin of many (shallow) fans who resent Capaldi’s age (he’s all of 56-years old). Though the 1st Doctor was portrayed by the then 55-year old William Hartnell in 1963, the show’s reboot saw 34-year old David Tennant and 26-year old Matt Smith change the role of the Doctor into a character surrounded by discourses of sexiness. The show itself deepened this association through romances between the Doctor and the young (emphasis on the coded-as-young) women who played his companions: an explicit relationship between the 10th Doctor and Rose Tyler (23-year old pop-icon Billie Piper), and ever-present sexual tension between the 11th Doctor and his companions Amy Pond (21-year old Karen Gillan) and Clara Oswald (26-year old Jenna-Louise Coleman).

In Capaldi’s first episode, the show rather heavy-handedly responded to fans’ ageism. The villains are ancient robots who have repaired their cybernetics with human organs for millennia in order to survive; their predicament prompts the Doctor to wonder if one is still the same individual if one replaces all one’s parts. Clara insists, “I don’t think I know who the Doctor is anymore”—and the show spends the rest of the episode berating her for it. The coldly pragmatic moral compass of the episode, Madame Vastra, castigates Clara: “He looked like your dashing young gentleman friend. Your lover even. […] But he is the Doctor. He has walked this universe for centuries untold. He has seen stars fall to dust. You might as well flirt with a mountain range.” The most telling moment, when the Doctor seems to speak directly to disappointed fans, comes at the tail-end of the episode:

The Doctor: I’ve made many mistakes. And it’s about time I did something about that. Clara, I’m not your boyfriend.

Clara: I never thought you were.

The Doctor: I never said it was your mistake.

I’m not the only one to recognize this as a gesture outside the text, but I would like to particularly call attention to that final line. The show passes some of the blame on itself: it coded the Doctor as sexy, and now, it has to step back from that.

Devotion to fans aside, capital is the core motive behind the message that the Doctor is still the Doctor even if he’s replaced all his parts. The franchise needs consumers to retain its enormous profit margin. To keep viewers tuning in (and buying commodities like my 10th Doctor Sonic Screwdriver pen), the message must be clear: we’re different, but we’re still the same; buy us.

The Republican Party has walked this tightrope for the last several years as they simultaneously cater to their base and try to attract new voters. A series of wonky and casually misogynist ads targeted women by painting Obama as a bad boyfriend, or Democratic candidates as hideous old wedding dresses that women need to cast off in favor of the sexy new Republican dress. I’ll leave out any actual discussion of the party’s thinking on race, class, and gender because in fact, as The Daily Show’s coverage of the election suggested, when it comes to branding, ideas don’t matter—money does.

This is not merely a matter of removing money from politics. When an election costs about $3,670,000,000 (writing it as $3.67 billion obfuscates the immensity of the cost), we’re talking brand marketing, not politics. Capitalist democracy gives the lie to arguments like Michel de Certeau’s theory of consumption as resistance, because here, consumption remains just that: consumption. Republicans offered a “new look, same great taste,” and voters happily purchased it. The parts are new; the Doctor is the same.

But Reince Priebus is not your boyfriend.

“Show me a good time?”: Madonna, Drake, and Police Brutality (18 April 2015)

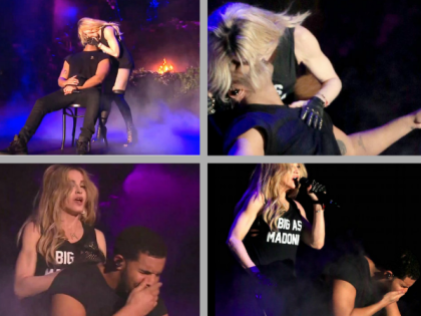

If you’re fortunate enough to have the self-control to avoid at least moving your cursor over the “trending” links on Facebook: apparently, Madonna kissed Drake at Coachella, and to paraphrase Drake “it was it was [sic] not the best.” I base that reading on Drake’s body language: stunned immobility, a wide what is happening gesture, and then hands on his lips, hunched over. Expertise in affect theory seems a bit unnecessary, here; his response could hardly be more overt.

I’m interested in this kiss not for the celebrity gossip, but because I see it an important piece of the current conversation about racism in the United States—and most importantly, as an important site for thinking about how to think through the intersectionality of oppression.

Walter Scott’s murder two weeks ago should ameliorate any reticence about the reality of violence against black men. As I listened to the NPR story, they announced that they were going to play an audio clip of the protesters, whom I fully expected to chant something about the police, or “black lives matter.” Instead, they chanted a different activist slogan and hashtag: All lives matter. This particular chant rose to prominence in response to the slogan “black lives matter” as a way to call attention to the broad oppression that marginalized populations face. In its brief life, “all lives matter” has received due criticism from private bloggers all the way through Judith Butler, who sums up the critique with succinctness that should shock anyone who has ever read Gender Trouble:

It is true that all lives matter, but it is equally true that not all lives are understood to matter— which is precisely why it is most important to name the lives that have not mattered, and are struggling to matter in the way they deserve.

To chant “all lives matter” in response to what is perhaps the most blatantly obvious in a series of state-perpetuated crimes that specifically target black men fundamentally misses the point: that these murders happen because black lives are readily swept aside in the flows of power that permeate American culture. Affirming life through mutual respect (a la Appiah) is a perfectly laudable ethics, but it does not address the tangible legal, institutional, and cultural issues that contribute to the systematic assault on black bodies. “All lives matter” is a positive message—but it but it offers a philosophical abstraction in response to a political problem.

More importantly, “all lives” flattens bodies through equivalence. In other words, in its attempt to find commonality, “all lives” erases difference. Cut back to Drake and Madonna. As the internet is wont to be, the internet was very confused about how to respond. Of course, many people suggested that Drake enjoyed it. Drake himself even posted an image on instragram, with the caption “Don’t misinterpret my shock!! I got to make out with the queen.” The picture Drake chose offers a brief moment that appears consensual in an event that seemed predominantly nonconsensual.

Some objected that Drake’s reaction implied that Madonna is disgusting, and so reinforced the idea that women cease to be attractive after they reach a certain age. The Huffington Post pointed toward John Travolta’s sexual harassment of Scarlett Johansson at the Oscars, and asked why Madonna received less criticism than Travolta. All of these responses are part of the same discourse: a discourse that flattens black bodies into mere intensities of violence and sexuality, and through that flattening, dismisses their bodies as bodies that do not matter.

Madonna’s kiss is hardly the first direct exploitation of black musicians by white musicians in recent (let alone longer) memory. I don’t mean the exploitation of culture, like Iggy Azalea’s bizarre code-switching (which Saturday Night Live fabulously lampoons), or the fact that every song Meghan Trainor sings is a poor rendition of doo-wop. I mean the exploitation of black bodies as sex-objects—the transformation of black bodies into just lumps of sexual matter. Think Miley Cyrus’s VMA performance, or Taylor Swift’s music video for “Shake it off” (intentionally not linked to images), which transform the black background dancers into mere ciphers for sex.

And here, we come to the sticking point. The Huffington Post’s article points fingers at an apparent gender bias, and asks: what if Madonna were a man, and Drake a woman? This is precisely the wrong question, driven by a similar impulse to “all lives matter.” Contrary to the impulse behind the discourses of sexual assault that have circulated around Madonna and Drake, one sexual assault does not equal all sexual assaults. Feminists, Madonna included, have struggled against the physical and emotional violence patriarchy directs at them; but that violence is fundamentally different than the violence directed at black men and women (which, of course, fundamentally differ from one another).

Madonna’s kiss was not sexual assault in the same way John Travolta’s kiss was: it was sexual assault in a different way. Violence against black men like Walter Scott is not the same as violence against black women, or Hispanic men or women: these violences differ. To argue that people should or should not be more or less upset because Madonna is a woman misses the critical intersection of race and gender. Drake is not merely a man; he is a black man in a culture that insists on coding black bodies as objects of pure violence and sex. Where a kind of pop-liberalism draws equivalence through common struggle, intersectionality underlines the political and pragmatic differences in the application of oppression.

The Dust-Heap of the Database and the Specters of the Spectator (8 May 2015)

In 2014, networks launched some 1,715 new television series, a staggering number that prompted many articles to declare variations on the theme “there are too many shows to watch.” Same story, different medium, I say. Franco Moretti, a contemporary literary scholar, writes that while twenty-first century Victorianists may (may) read around two-hundred Victorian titles, that barely counts as a drop in the bucket of the 40,000 titles published in the nineteenth century. And the other 39,800 novels? The short version: gone. The longer version: maybe not.

The plethora of “lost” Victorian novels challenges any sweeping claims about Victorian society based on the fourteen or so (depends on how you count) full-length novels of Charles Dickens. But it becomes even more daunting if one’s studies include explorations of Victorian popular magazines and journals. The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals 1800-1900 lists 50,000 titles. If each of those titles published a single, twenty-page issue—and certainly they published more—that alone would amount to 1,000,000 pages to read.

The imbalance between what we read, what we could read, and what we can’t read makes Victorian studies (and, I suspect, other historical studies) a strange beast. Any decent Victorianist monograph will address the familiar tunes (Dickens, the Brontës, Eliot, etc.), but it will probably do so through ephemera and periodicals that maybe only the author has read thanks to hours of archival digging. The internet makes the strange Victorian studies beast even stranger. The internet not only changes how I do history because I can do most of my archival work from the back corner of Mello Velo (the local coffee shop, to which I owe my doctorate, whenever I finally defend). Historical research online changes academic reading practices, the kinds of arguments we can make, and finally, how we teach historical reading in the classroom. Internet archives make available texts virtually nobody has read. Electronic archives offer the chance to reinvigorate the dust-heap of forgotten novels—although with the change in what we can read, there comes an inevitable and sometimes ineffable change in how we read. It also makes it possible to discover a text nobody has read, without leaving the comfort of your favorite coffee shop table.

And yet, when I say a text nobody has read, this isn’t quite true. These texts do not simply appear on one’s screen. These historical documents already bear the marks of their nineteenth-century readers, but they now bear the marks of my search terms, the database algorithms and tags, scanners, computer processing, and somewhere in a basement, other people who plugged this material into the database. These extra, mostly ineffable hands mark the text like the fingerprint of electronic ghosts—and these spectral hands can sometimes offer us bizarre, fortuitous accidents.

Here’s an example. My dissertation is in part about Charles Dickens, because of course it is. I’m also heavily invested in Victorian literary criticism; that is, as opposed to Victorianist literary criticism of the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries, I gravitate toward the theories and ideas the Victorians themselves used to analyze their own work. I’m specifically interested in Dickens’s serial publications (stories told in installments, like a modern television show), and I wanted to see what the Victorians thought about serialization.

So, off I go to sundry databases and metadatabases, where I search terms like “serial,” “part,” “periodical,” “novel,” and “publication.” As part of my search, I examined the Spectator Archives(1.5 million pages, by the way), where I found this priceless artefact: “Doe’s Oliver Twist.”

Wait, didn’t Dickens write Oliver Twist? you ask. Who on earth is “Doe”?

Welcome, Dear Reader, to the dust-heap of the archival database. Archives like the Spectator Archive use something called Optical Character Recognition (OCR), which is the process by which a computer converts scanned images of pages from something like an 1838 edition of a magazine into searchable text. It’s built in part by programs like reCAPTCHA, the obnoxious text you have to enter before buying or registering at some websites to prove that you’re a human, because only humans scream obscenities at their computers after the thirtieth failed entry. It’s pretty incredible, when you think about it.

And it’s also terrible, as proven by the title: the Spectator Archive’s OCR rendered “Boz” as “Doe.” Wait, didn’t Dickens—

Yes, Dickens wrote Oliver Twist. But before that, he published Sketches by Boz, a series of wonderfully liberal musings on life in London. And so, when Dickens began to serialize Oliver inBentley’s Miscellany in 1837, the author’s name was “Boz.” But the Spectator Archive doesn’t know that. In fact, it doesn’t know anything. It’s a scanner, and a computer that runs OCR software, tags its garbled production, and then throws it into the ether for some random grad student to stumble across. And behind that, someone—probably a random grad student or intern—in the basement of the Spectator building on Old Queen Street—could have read this article. Because someone had to put the page on the scanner and press “go.” Behind the Spectator is a series of spectral readers: the Victorians who may have read the article in 1838, the person who scanned the article, the scanner, the computer, the series of algorithms and programs that brought me from Google to the Archive and to that article.

“Doe’s Oliver Twist” is a gold-mine for Victorian theories of reading, serial publication, and distinctions between common readers and academic readers. But in order to find it, one has to enter the right search terms, and—here’s the real punchline—those search terms may abound in a document and not show up in the algorithm because the OCR is wrong. But there’s one final twist, and it isn’t Oliver.

In fact, “Doe’s” showed up in my search results because something was OCR’d incorrectly. While it thought it recognized one of my terms, in fact, that term does not appear in the document.

Internet archives allow scholars to dive into the dust-heap of history. In their clunky, unintuitive ways, they cough up garbage and leave us to sort the mess. And as I will argue in future posts, they fundamentally alter the ways we perform these readings. Welcome to twenty-first century history: a tangled heap of trashed treasures and treasured trash.