Lindsey Decker

Lindsey Decker is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate studying Film and Television in the Department of English. Her dissertation examines questions of transnational cinema in self-reflexive British horror films.

To read and comment on Lindsey’s posts individually, please use the links below:

Rude Wastes of Space: Race, Class, and the Othering of the British Hoodie (6 Jan. 2015)

Nightcrawler: Not the Satire You Think It Is (20 Dec. 2014)

Feminism doesn’t (t)werk that way: “Booty Culture,” race, and pop feminism (12 Dec. 2014)

Feeling Testy: Assessing our Assessments (5 Dec. 2014)

Rude Wastes of Space: Race, Class, and the Othering of the British Hoodie (6 Jan)

One of the more interesting parts of writing my dissertation so far has been investigating the phenomenon of the British hoodie. My dissertation focuses on the post-2000 British horror resurgence, and the hoodie horror cycle has been one of the more prolific cycles within the more general boom.

Menhaj Huda’s 2006 film Kidulthood is often identified as one of the first hoodie films.

Hoodies are usually working-class teen delinquents who wear hooded sweatshirts. During the first decade of the 2000s, hoodies became prevalent in a variety of forms of British popular culture. There were frequent news stories citing hoodies as a consequence and contributor to “Broken Britain,” a cultural discourse that maintains that Britain is more lawless, chaotic, and dangerous than ever before. Cinemas screened films like Kidulthood (Menhaj Huda, 2006) and Harry Brown (Daniel Barber, 2009), while various television channels produced and aired programs like Misfits (2009-2013, E4) and the reality series Kick Ass Kung Fu (2013, Sky1 HD), wherein a Shaolin monk trained hoodie-clad teens from “bad areas” to channel their aggression and stop being “rude waste[s] of space,” as one of the show’s hoodies put it. Even Piers Morgan produced and directed a documentary on hoodies for Sky1, Hoodies Attack (2005). At least one London gym began offering a much-publicized “Chav Fighting” class wherein middle class customers could learn to put the world to rights, while the Thames Valley Police had their officers swap their uniforms for hoodies and tracksuit pants in an attempt to blend in and stop anti-social behavior (though the officers did not wear baseball caps, which were thought to make them look “too American”).

Like the Teddy Boys, punk rockers, and, most recently, the club kid ravers, hoodies are set apart from so-called normal society. The Teddy Boys’ association with the rise of American rock and roll, and their reported rioting and dancing in theaters’ aisles during screenings of Blackboard Jungle (Richard Brooks, 1955), positioned them as importing the dangerous violence of American teens via the bad influence of American rock and roll. In particular, their sartorial borrowings from the African-American community set out their cultural borrowings as dangerous not only because of their Americanized nature, but because of their origins in communities of color.

Source: Flashbak

Hoodies are set apart by their mode of dress (face-obscuring hooded sweatshirts), their musical preferences (most often assumed to be rap and hip-hop), and an anti-authoritarian attitude that sometimes places them on the wrong side of the law. And, much like the moral panic surrounding the Teddy Boys in the 1950s, fear of hoodies belies not only a fear and distrust of young people but a fear of the Americanization of British culture.

Still from Johannes Roberts’s hoodie horror film F (2010)

Hoodie teens are seen as having brought American gang culture, as promulgated by American rap and hip hop and American films, to the streets of the UK. In particular, the UK garage music scene was seen as, in the words of political and social commentator Deborah Orr, a “bad-seed” offshoot of UK youth culture that is heavily influenced by US gangsta rap culture (or at least seen by middle class commentators as heavily influenced by gangsta rap). Of course, UK garage music, because of its perceived links to US gangsta rap culture, made an easy scapegoat, and condemning UK garage for promoting violence was a way to more implicitly condemn the working class urban populations and racial and ethnic minorities who listened to UK garage.

Hoodie horror films often signal this link between hoodies and Americanization through rap-heavy soundtracks or having the evil hoodies listen to or perform rap in the diegesis. For example, in James Watkin’s Eden Lake (2008), the hoodie gang brings a boom box to the beach and plays rap music; this music plays at a lower level of the sound hierarchy, just loud enough to act as a menacing, unintelligible buzz that haunts the scene and foreshadows their coming attack on the middle class protagonists Jenny and Steve.

The imagery of hoodie horror mirrors the aural distinctions between the Americanized hoodies and their respectable victims. In this image, the trailer serves as a clear visual delineation of the line between acceptable, middle-classness, as represented by Jenny on the right, and the film’s villains, on the left: the unacceptable, Americanized, working-class hoodies who antagonize and torture Jenny and her boyfriend throughout the film.

These links to Americanization make it even easier for the media (as well as some filmmakers and audiences) to Other hoodies; they are not only working-class and young, but they can be seen as more influenced by American and Americanized culture than respectable middle-class Brits. Of course, this Othering places an additional mark upon hoodies of color, who are already also Othered by their racial and/or ethnic status.

Nightcrawler: Not the Satire You Think It Is (20 Dec)

On its most basic level, Nightcrawler (Dan Gilroy, 2014) is a heavy-handed satire that indicts the “if it bleeds, it leads” mentality and the normalization of violent and gruesome images on television news. Since images of the Vietnam War made their way into people’s homes via television screens, there have been debates about how much is too much, and what you can and cannot show, ethically, on television.

However, Nightcrawler also contains a much more interesting satirical thread in the figure of its ruthless entrepreneur Lou Bloom*, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, a young man who starts filming accident and crime scenes and selling the footage to the news. The film satirizes the discourse of bootstrapping and “job-creating” entrepreneurism that rose (from its continual background presence) to particular visibility during the 2012 presidential campaign. The last campaign may seem like a distant memory for many, particular given our 24-hour news-cycle mindsets. My students this semester didn’t even remember “binders full of women.”

Remembered or not, the Romney/Obama campaign cycle focused heavily on how to lift the country out of the Great Recession. For Romney, that meant eliminating the minimum wage, increasing unpaid internships, and stimulating private-sector entrepreneurs to create the jobs and reduce unemployment. He was skewered by liberal and mainstream media outlets for depicting himself as having bootstrapped his way to riches (“Everything that Ann and I have, we have – we earned the – old fashioned way. And that’s by hard work”), for advising college kids to start businesses by borrowing a little money (like, $20,000) from their parents**, and for his now-infamous 47% remarks. Discursively, Romney was framed as a man who didn’t care about the average American, or the average employee, and who promoted a broken and ruthless brand of entrepreneurial capitalism that would serve to make the rich richer without improving the lives of “average” people.

Image source: Mitt (Greg Whiteley, 2014; available on Netflix)

Nightcrawler takes the ideas espoused by the Romney campaign, and the discursive fashioning of that campaign by an unsympathetic press, to their logical extreme. Lou starts the film unemployed; he has turned to stealing manhole covers and copper wire from abandoned buildings to make money. But he’s also self-educated, having combed the wealth of the internet and imbibed all of the employment advice and entrepreneurial common sense he could find. Early in the film, as he tries to weasel his way into a job at the scrap yard where he is selling his ill-gotten goods, Lou gives his elevator speech:

“Excuse me, sir. I’m looking for a job. In fact, I’ve made my mind up to find a career that I can learn and grow into. Who am I? I’m a hard worker, I set high goals and I’ve been told that I’m persistent. Now I’m not fooling myself, sir. Having been raised with the self-esteem movement so popular in schools, I used to expect my needs to be considered. But I know that today’s work culture no longer caters to the job loyalty that could be promised to earlier generations.”

Lou’s words appear benign. Who among us doesn’t want to think they are a hard worker who sets goals and has persistence? And Lou seems humble, actively countering the anti-millennial discourses that indicts that generation for its entitlement and narcissism. He’s a go-getter, what critic Anthony Lane calls “an entrepreneur, in a fine, self-improving American tradition.” But Lou is also ethically blind—he cannot understand that the scrap yard owner won’t hire a thief.

Also, he’s super creepy looking.

Lou’s hard work, high goals, and persistence eventually lead him to blackmail and sexual exploitation. After selling one short clip to a news channel for a few hundred dollars, he begins to tell people he runs “a successful TV news business.” He hires an unpaid intern, Rick (Riz Ahmed), continually promising a promotion and a wage that he never intends to deliver. When he tells Rick that “Good things come to those who work their asses off,” it isn’t a motivational truism but a thinly-veiled physical threat. Lou is a capital creator and brand creator (with his company’s name, Video News Production), but not a job creator, and certainly not a nice-guy bootstrapper who plans to pull others up with him.

Like the high-profile white collar professionals who brainstormed the subprime mortgage fiasco that contributed to the Great Recession, Lou exhibits a reckless disregard for ethics and the well-being of others, and this recklessness leads him to financial success. Some critics have taken Lou for a sociopath or as suffering from some other mental illness. However, pathologizing the character undercuts the film’s satire and denies the pervasiveness of this sort of mindset within corporate America. Lou’s “sociopathy” is just everyday corporate practice, and his big break delivers a stinging satirical bite: Lou makes his break while exploiting an affluent white family. The second set of footage he sells to the news networks to conclude the story makes him enough money to expand his operation by investing in several vans…and several more unpaid interns. His big break shows that no one is safe from his unethical entrepreneurism, regardless of class or economic status, cementing the film’s reactionary liberal satire of the sort of values that Romney embodied and promulgated on the campaign trail.

*Yes, James Joyce’s Ulysses and Leopold Bloom resonates here as well, the wandering man drifting through his city.

**This incident, while still definitely indicative of class and economic privilege, was pretty overblown by some media sources. Romney was telling the story of Jimmy John, the sandwich shop owner and franchiser. Romney said, “We’ve always encouraged young people take it, take a shot, go for it. Take a risk, get the education, borrow money if you have to from your parents. Start a business.” In this story, though, he also said that Jimmy John, “said he borrowed $20,000 from his dad” to start a restaurant, and it didn’t seem to occur to Romney at the time that a pretty high percentage of American parents cannot give their child $20,000 because they’re living paycheck to paycheck, or are underwater on their mortgage.

Feminism doesn’t (t)werk that way: “Booty culture,” race, and pop feminism (12 December 2014)

As Pippa Middleton recently remarked, “What is it with this American booty culture? It seems to me to be a form of obsession.”

Who doesn’t love the booty?**

Whether we’re talking about Miley Cyrus’s twerking, Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda,” Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass,” Jennifer Lopez and Iggy Azalea’s “Booty,” Kim Kardashian’s “break the internet” photos, Rihanna and Shakira’s “Can’t Remember to Forget You,” or even Taylor Swift crawling between the legs of her mostly black twerking dancers (whose faces we never see) in “Shake It Off,” the discourse of the “booty” is currently almost everywhere in mainstream American culture. One half expects to see mainstream television programs take up the issue in a bid for ratings. Next week on Modern Family: the token angsty teen girl is even more angsty than usual because her step-grandmother has a better butt than she does.

Image credit: DeviantArt user A-Little-Kitty

Vogue has declared, in fairly jejune fashion, that the booty obsession is just the fulfillment of discourses we weren’t ready for 13 years ago — we weren’t “ready for the jelly” in 2001 when Destiny’s Child came out as “Bootylicious,” but we are ready now that J.Lo and white rapper Iggy Azalea are asking us to “Throw up your hands if you love a big booty.” Nicki Minaj is the fulfillment of the promise of J.Lo’s green Versace dress.

Others, including Yomi Adegoke and Susana Morris (of Auburn University, and co-founder of the generally awesome Crunk Feminist Collective) have discussed the booty obsession as cultural appropriation of what has been a desirable body type within black American culture. This appropriation was made perhaps most clear when Miley Cyrus, who has been donning the trappings of black rachet culture for several years now, photoshopped Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda” cover photo, literally whitening Minaj’s skin and replacing Minaj’s face with her own. (The racism in the Kim Kardashian photos is also strikingly baldfaced.) The racial appropriation within “booty culture” is more than troubling, particularly during a time when the most pervasive images of black people within mainstream culture are photos of men like Michael Brown and Eric Garner, or the young Cleveland boy with a toy gun who was shot seconds after police arrived on scene. What has come to be thought of as the “black body type” in our culture has become acceptable and celebrated in the mainstream, but this (and other) cultural mainstreaming has not affected the systemic racism that oppresses black Americans. Mainstream culture incorporates and makes equally-available the body type without truly incorporating or making equal the bodies themselves.

Also, the sudden pervasiveness of “booty culture” seems suspicious given how it has taken focus off of the previous, somewhat overlapping female pop star controversy: contemporary feminism. Regardless of whether we personally think Beyonce‘s, Taylor Swift‘s, Miley Cyrus’s, Pharell‘s, Rihanna’s, or Nicki Minaj‘s feminism is substantively advancing equality or just substantively cashing in on millennial desire for commodity activism, conversations were taking place. There were daily opportunities to discuss *feminisms* and break out of the post-feminist backlash discourse of “one man-hating sexually-repressed feminism only for women who are just angry that they can’t consume their way to pretty.” The everydayness of pop feminism, and yes, the trendiness, created space for these conversations to be framed as relevant and timely.

Over the summer, articles were calling 2014 the “year of pop feminism.” Now, it is the year of the booty. Yes, the booty obsession has emphasized “different body types.” But the focus remains on the body. For women, the body is an asset, a marketable commodity, but that also makes women, to some extent, an object, playing into the traditional “to-be-seen”-ness, the “desire to be desired” (to use Mulvey and Doane’s phrases).

Thus, Beyonce’s last album, which contains a voiceover with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie explaining the definition of feminism, discursively becomes the album wherein she started a song with the lyric “Let me sit this ass on you.” Tthe conversation returns to its cultural comfort zone — not how we could achieve gender equality so neither women NOR men are disciplined or punished into outmoded and damaging gender roles, but how women can empower themselves by, in bell hooks’ words, playing into “tropes of the existing, imperialist, white supremacist, patriarchal capitalist structure of female sexuality.”

** This post contains no photos of booty. The writer does not wish to participate in the continued objectification of other women by including gifs or images that turn those women into faceless body parts or mark out their bodies as exchangeable.

Feeling Testy: Assessing our Assessments (5 December 2014)

Tests and assessment make people angry.

No really — tests, and the entire idea of assessment, can produce positively splenetic displays. The comments section of Christopher B. Nelson’s recent essay critiquing assessment provides an apt example. As the federal government pushes to hold colleges responsible for providing students with the best “value” for their dollar, and universities push assessments in order to prove (or expose a lack of) efficiency and excellence, it is easy to shout “crisis!” It’s equally easy to imagine testing companies’ CEOs and CFOs salivating over the money to be made from implementing standardized tests to assess whether university students have met desired (perhaps national) learning outcomes. Common Core Goes to College.*

I have a vexed relationship with testing. I’ve helped edit and write tests professionally. I also majored in secondary education at a school that emphasized a modified-Constructivist pedagogy; I was taught that learning is an active, continuous, individual process shaped by students’ previous experiences and which cannot be assessed using a tool that punishes or unduly stresses students. While there are valuable ongoing high-level conversations about assessment, including what sort of assessments are the optimal measure of learning (multiple-choice versus essay, national standardized tests, measures of student engagement, etc.), I want to focus on an assessment instructors control: midterm and final exams.

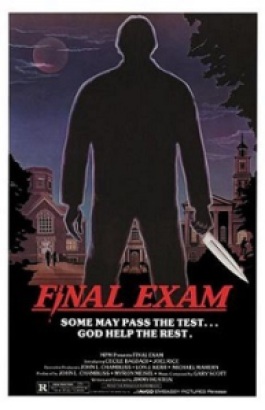

Exams: one of the many things that has killed Sean Bean.

Take my intro-level film course. To produce nuanced interpretations of films (a major learning outcome of the course), students must be able to apply a vast store of terminology relating to the compositional elements (sound, editing, cinematography, and mise-en-scène), as well as terms relating to broader processes. No essay assignment, or even series of them, could realistically require the use of even three-fourths of the course terms. I’ve found that even when students correctly define and apply a term on their quizzes and exams, they still might not do so in class or essays. I’ve administered a range of quiz types (multiple-choice, short answer, brief essay) and spent days crafting my exams, but I wasn’t satisfied that I was accurately measuring my students’ learning. During a final exam review session, surrounded by my sweating, overly-caffeinated students, watching them scribble down, word-for-word, the answers they and their peers provided to their practice questions, I realized maybe one culprit was the sort of memorize/regurgitate/forget culture tests can perpetuate.

Last semester, I taught the course again and tried a tactic I hoped would decrease student anxiety and increase net learning. Throughout the semester, I emphasized the ways in which our class discussions, short papers, and tests were all opportunities to confirm or refine their knowledge of course terms so they could produce exceptional final essays. At midterm and finals, my students took an individual and a group exam. If a student achieved a set score on the individual exam, then I would average their individual and group scores to calculate their overall exam grade (though only if it improved on their individual score).

During the group exam, they were instructed to talk through each answer to come to a consensus, so that students who made mistakes on their individual exams would be corrected by their peers. The exams themselves were a mix of short and long answer questions. For example: Identify 15 of these 20 terms in your own words and provide, for each, an example from a film screened for class. The individual exam was still a scene of frenzied writing (and sweating), but the group exam was a scene of teaching. Students argued about the difference between a long take and a long shot and whether US cinema had widely adopted color film stock during the Golden Age or after WWII. I took the questions most often answered incorrectly on the midterm and incorporated them into the final exam. For example, to see if they had finally grasped high versus low key lighting: List and describe four formal conventions of film noir, one of which must concern lighting, using appropriate terminology.

Images from http://filmschoolonline.com.

In class, in essays, and on their tests, my students deployed course terms with more frequency and accuracy. On my evaluations, students frequently cited these exams as both less stressful and more conducive to their learning, particularly because of the way in which they had to explain their answers to their peers and pool their collective brainpower. Some students will always see tests as an exercise in short-term memorization, and standardized assessments continue to creep into higher ed, but I think the current assessment fad is a valuable opportunity for us as instructors to examine and potentially revise our course assessments to assure they are best serving our and our students’ needs.

* Note: I am using Common Core here metonymically to represent the whole media discourse of “bad testing” — the Common Core Standards themselves present a much more complicated set of issues, and I’m not commenting on their relative merits or demerits in this post.

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- September 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- October 2023

- May 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

Leave a Reply